Check out my latest review in Provincetown Magazine for John Krasinski’s absorbing horror film A Quiet Place. It’s playing not only in Provincetown, but everywhere, and you simply cannot wait for it to be online/DVD… it demands the cinematic environment.

Check out my latest review in Provincetown Magazine for John Krasinski’s absorbing horror film A Quiet Place. It’s playing not only in Provincetown, but everywhere, and you simply cannot wait for it to be online/DVD… it demands the cinematic environment.

Month: April 2018

The Godard Connection

Louis Garrel as Jean-Luc Godard in Godard Mon Amour by Michel Hazanavicius, a Cohen Media Group release.

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote a blog post about the ongoing internal debates I have about why movies matter, why I write about film, why I make films, etc., etc. Just a few days after writing that post I was offered a screener of the new film by Michel Hazanavicius, Godard Mon Amour (a.k.a. Redoubtable). The film is based on the 2015 book Un an Après Anne Wiazemsky wrote about her love affair with and subsequent marriage to one of France’s most famous directors and general provocateurs, Jean-Luc Godard. Their relationship came about in the late 1960s, and the focus of the film is the political upheaval in Paris in May of 1968, leading to the cancellation of the prestigious Cannes Film Festival in response to student and worker protests in Paris. It struck me as incredibly serendipitous for me to come across this film at this particular moment, as what emerges through the story is a Godard undergoing a reevaluation of his life, his work, and the meaning (or lack thereof) inherent in making, talking about, writing about, and seeing films.

The film begins with a huge title saying “Wolfgang Amadeus Godard,” cluing us into the geni

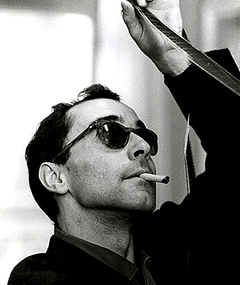

The real Jean-Luc Godard

us of Godard in a tongue-in-cheek manner. Louis Garrel (son of French New Wave director Philip Garrel) plays Godard as arrogant, self-centered, and rather obnoxious, but at the same time he reveals a deeply committed artist who, like the rest of us, is uncertain about his relevance in the world, vulnerable, and awkward. As he walks in solidarity with student protestors vastly younger than him, he is supportive of them politically and philosophically, but at the same time reluctant to pass the torch. His relationship with Anne (Stacy Martin) is passionate, but at the same time Godard doesn’t really see her for who she is. It is in this context that Godard goes to Cannes at his wife’s urging, although he feels it is ridiculous to go to a film festival when there is violence in the streets, and a revolution is in the making. He goes, but along with several notable directors, shuts down screenings and convinces the jury to officially end the festival several days earlier than planned in the name of solidarity with protestors and, in a sense, an acknowledgement that the festivities do not align with the important debates and issues going on in contemporary French culture.

Hazanavicious, whom I interviewed for Cineaste several years ago in regard to his modern-day silent film The Artist, has a knack for bringing cinematic history to life using a clever interplay between form and subject matter. In The Artist, he told the story of silent actors on the cusp of obsolescence as the Sound Era arrives, and he did so in a silent (except for one part) black-and-white movie. With Godard Mon Amour, again Hazanavicius connects story and cinematic form by creating a movie about Godard that follows the style, idiosyncrasies, and self-referential nature of Godard’s own best known films from that period. For example, in a scene in which Godard and Anne discuss whether or not the nudity in a script she’s reading is justified or simply gratuitous, the two walk around stark naked. It is this kind of self-reflexivity in Godard’s films that really made his work so uniquely “a Godard film.”

Godard Mon Amour feels particularly relevant now in this country even as it is about something that happened 50 years ago on another continent. As we see our own, albeit less dominating, student revolt and watch the astounding responses to it, any thinking artist is wondering about the role of art and cinema in divisive times. With every day bringing forth another horror from somewhere around the globe, another reason to question our work and our futures, Jean-Luc Godard’s concerns have never seemed more relatable than they do here. It’s not only his existential angst that resonates, but also the enfant-terrible arrogance invites some thought about separating great artists from their personalities and whether or not that’s possible.

But contemporary sociopolitical dialogues aside, Godard Mon Amour also succeeds in reminding us what was so endearing about Godard’s work and about the French New Wave itself. There’s humor to it. It’s not all theoretical cinephilia, even as that serves as a basis for much of his work. At the end of Godard Mon Amour I immediately yearned to watch Godard’s films again. Although I adored the last film I saw by Godard, his 3-D Goodbye to Language, it is those earlier, daring films I saw in film school that I craved most. Doing so did wonders for my cinematic soul, and I hope you’ll revisit them as well, especially Masculin Feminin, Pierrot le fou, Alphaville, and of course, Breathless.

Godard Mon Amour opens in New York and Los Angeles on Friday, April 20, and will open at the Kendall Square Theater in Cambridge, Mass., shortly thereafter.

Time’s Up

I recently attended the Provincetown Women’s Media Summit and had the chance to speak with two keynote speakers, Dr. Stacy Smith and April Reign, about increasing diversity and opportunities in the film industry. The article appears in Provincetown Magazine this week. Here is the link. Check it out!